SALON DOGS

Statement by Susannah Martin

It was the realists who first challenged the academy and the official Salons´ monopoly of power over public taste in mid- 19th century Paris. Famously, the impressionists drove the nails in the coffin. Realism, as opposed to the then reigning conglomerate neo-classical/romantic style of painting, shocked the establishment with its´ focus on contemporary ordinary life in all its´ crudeness. With Corbet, began the revolution of the „ now “, which has continued throughout the 20th century and is more active than ever in 2015.

The French Academy and the Salon de Paris were essentially one institution designed to „ monitor, foster, critique, and protect French cultural production“. In other words, they were the beauty police. The acceptable subjects for paintings were generally considered; history painting, portrait, the nude in the form of an ancient Greek god or goddess, and tidied up landscapes. My subject matter clearly places my work in line with these militaristic guidelines for art and raises some questions regarding my respect for modernism. Certainly, my German colleagues, will verify their suspect feelings and fascist associations which bother them when confronted with a figure painted in a “neo-classical” style.

For me, the French Salon remains a symbol of all tendencies in the art world and in society which attempt to dictate an aesthetic beauty norm. For example, I tend to think of our massive fashion and beauty industry as being fueled by contemporary salon mentality. We have a tendency to seek out an expert or chief of police to employ his ruling hand and inforce norms on this rowdy and divergent crowd of struggling and imperfect humanity. And yet, whenever the beauty police become too strong, the heart of the revolution begins to beat louder and the realists come out of the closet to overturn the system.

The question, however, of defining realism right now, is a tricky one. What does our world look like these days? From a 19th century perspective, one would have to say that our concept of reality is warped, fractured or twisted. Or is it perhaps expanding? Our concept of reality now includes vantage points which would have been unrecognizable to our 19th century brothers and sisters. For example, would they have been able to recognize wine flying through the air captured at a millifraction of a second with a high speed camera, as wine at all? No one living today has trouble interpreting this odd shaped image. We cannot define contemporary reality without mention of the internet or photo manipulation. Our minds have learned to form new and unexpected associations between seemingly unrelated images at a constantly increasing rate.

The crowded house of images which now occupy our minds and make up our concept of reality feels like a bawdy three ring circus show compared to the orderly Tableau of the 19th century. It is difficult for us to fit our concept of life back into that picture frame. As a painter who grew up in a family of artists and received a still rather formal academic fine arts education, my painting techniques are usually described as classical. The people in my paintings clearly are distantly related to those of the Salon, but they are more the bawdy revelers of contemporary society. We are more likely to find them obstructing and disturbing the bucolic landscape than peacefully coexisting as they used to in the forest of Fountainebleau. As I attempt to preserve a romantic landscape for my viewing pleasure, they burst in with all their awkward struggles to cope with an ever expanding virtual reality. They bring with them their ever present dogs, mans´ strongest ally and remaining link to the natural world.

From the front of the revolution of the now I can only make the following report; the dogs have been let loose in the Salon and the police are impotent to stop them. The Salon has metamorphosed into an Art Fair and the revelers have taken control.

Susannah Martin

PRIMORDIAL TOURISTS

"In every human heart, lives something of the longing

to return to his place of origin,

after all the alienation from God and from ourselves

to find our way back to our eternal home"

Felix Schlösser

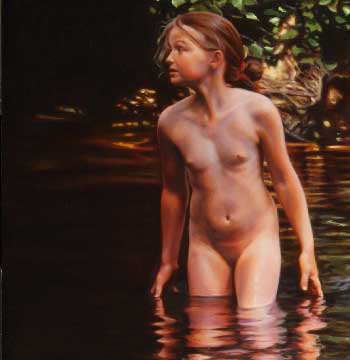

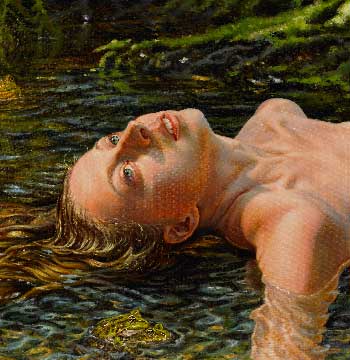

The history of the painted nude in landscape documents exactly this eternal longing. Setting aside for a moment, any erotic motivations, the nude has always also been a symbol for man in his purist form, his original form, his primordial form. Stripped of all social indicators; clothing, possessions , etc., he exists independent of identity in a time of pure being. Being is our eternal home. Nature does not possess an identity, it is. The nude in a natural setting has always been associated with our return to a time of pure being, a return home.

I have always been fascinated by how artists throughout human history have chosen to represent our interconnection with nature through the nude and how these choices reflect their epoch. For the primordial artist, nature was home. When he drew images of man and beasts on cave walls with charcoal and fat, he was merely recording his daily experience in his natural environment. That his stick-figure hunters and their voluptuous mates should be as nude as the animals he observed was never in question.

The human form in ancient Egyptian art shows to what degree man still felt at home in his unity with the forces of the universe, all of which he identified in an endlessly complex network of gods and deities of nature. Although he knew that his every movement took place in a state of interdependence, his feeling of separateness was slowly being made apparent through the introduction of a delicate sheath of cloth around his hips. Regardless of how thin and translucent the fabric, or how faithfully it clings to his form, the statement is irrefutable and irreversible; the separation of man and nature is inevitable.

By 400BC, the Greeks had brought the nude to its most elegant perfection and removed it firmly from any contact with earth and animal life. No God would need to hunt for his food himself and the beauty of a human athlete could grace nothing less than center stage in the amphitheater. Mans´ separation was established, his position was now far above and in command.

Following this terrifying proclamation of independence from nature, came a long period of silence regarding how the nude should be represented, known as the dark ages. The Renaissance began with a resounding affirmation of ancient Greek philosophy. Man was once again the apotheosis of beauty and yet was forced to unify with newly formed Christian ideals. Man must be seen as part of all creation though made in the image of the father.

Slow attempts were made to re-unify the nude with nature which came in two categories; references to Greek mythology or biblical illustration. These two varieties competed for center stage until a new agitator began to appear on the horizon: industrialization. The artists of the Romantic movement, living at the dawn of the industrial revolution sensed what was coming and with visions of Rousseaus noble savage fresh in their minds vehemently tried to bind humanity to his natural origin through music, poetry and painting. A new concept of the nude began to emerge, born of its´ Greek mother and biblical father, but more human and contemporary: The Bather, a man or a woman, made timeless through nudity, unadorned in non-heroic interaction with nature. The Bather is a direct descendant of the hunters of Lascaux and has remained throughout the centuries a link to primordial man.

It is no wonder that we associate The Bather with the romantic movement but he would reach his apex of popularity in the late 19th century just as industry was in its most powerful and destructive phase of expansion. But while the 19th century could still represent a plausible bather in a secluded natural setting, the 20th century witnessed the collapse of this ( selbstverständlichkeit) naturalness. The modern psychosis began; our human psyche split between the fear of loss of origin and the exhilarating thrill of technological advancement. A plausible union of man and nature in art could no longer be taken for granted. The absurdity of the image grew in direct proportion with the advance of science and urban sprawl The invention of photography pulled artists into realism and then pushed them into abstraction.

Nature is no longer home to us, she is much more a tourist destination. Certainly no representation of the nude in landscape in the 21st century can escape conveying our extreme estrangement from nature, intentional or not. There is an unavoidable strangeness or feeling of dislocation which envelopes the most sincere attempt at harmony. How absurd man seems stripped of his possessions and identity crutches and yet it is indisputable, he gains strength, clarity and beauty whenwe contemplate him abstractly , as a phenomenon of nature. My experimentation with contemporising the nude in landscape takes place within this framework of tension between these two poles of self-perception.

It is the rise of the virtual world which has permitted artists to bypass any mandate of plausibility in representational painting. If man can now appear as an intergalactic android engaged in battle with an alien species he may also go bathingin a local stream. It IS realism, if we accept that realism now includes virtual realism, that is it incorporates a high degree of improbability, a hyperbolic realism. Man may return once again to his original landscape, his eternal home, all be it this time as a tourist, a primordial tourist.

Susannah Martin